Barking is part of the Borough of Barking and Dagenham in Greater London, situated to the east of the city at the very end of the District and Hammersmith and City line. In 2004 we went on our first muf site visit – to a carpark for Barking’s town hall. This strange place read as a back land, standing as it did to the rear of shops, with flats above, which included a funeral parlour with its horses, and a fish shop that stood where the arcade now stands, which had a black and white tiled floor. This is echoed in the floor of the new arcade, and many of our projects have these memorial qualities, like an archaeology of the unimportant world – celebrating the fragile can have these repercussions.

The public space now called Barking Town Square sits in front of the town hall, where this carpark once was, and occupies the spaces between the new buildings of the town centre development. It was built in four stages between 2006 and 2010, and muf continued to work on satellite projects in Barking’s town centre until 2013. The town square is a T-shaped space of 6000 m², and is composed of four overlapping elements:

the civic square, the arboretum, the folly wall, and the arcade, each of which is described in the Catalogue of Parts. (see fig. 1 for location). The phases in which it was built did not correspond to these discreet elements, however, and each phase of the public realm was dependent on and a requirement of the private housing, one triggering the other. The delivery of the square was part of the initial phase of a larger redevelopment masterplan to provide high to medium density housing of approximately 500 new homes, a newly-built library, a one-stop shop providing community support, a children’s and primary health centre, accommodation for

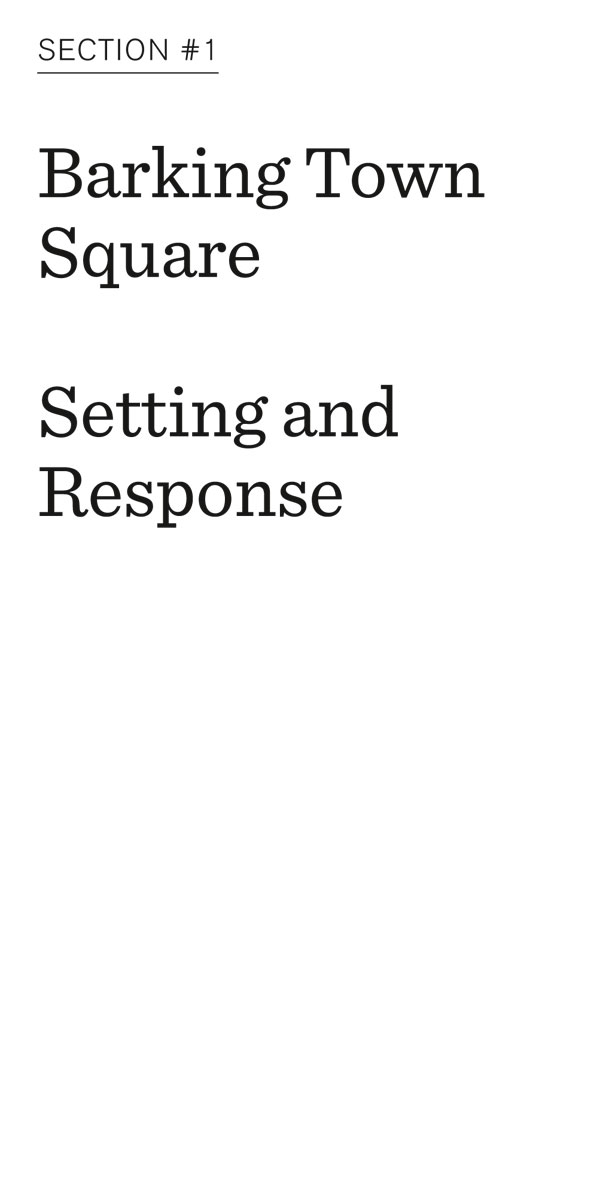

fig. 1 – Site plan

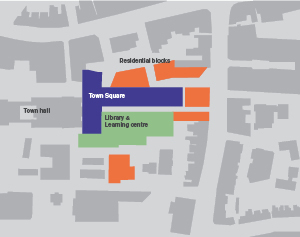

fig. 2 – A route and a destination: this plan shows the shade and airflow inbetween the new buildings.

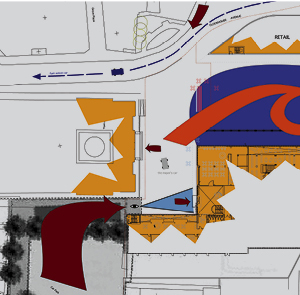

fig. 3 – View to AHMM’s residential block

over library phase 1

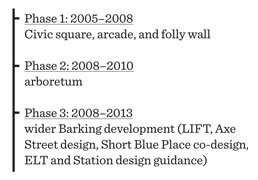

fig. 4 – Timeline

the University of East London, a hotel, shops and cafes. (fig. 3 shows phase 1 of the masterplan, Allford Hall Monaghan Morris Architects – AHMM’s residential block over the library, under construction.)

Having had no private investment for 60 years, funding for the redevelopment came all at once: masterplans were made and we were able to contribute to the wider planning through the square. This acted as exemplar both as the space itself, but also as an illustration of principles (which is partly recorded in the Barking Code). Funding for phase 1 and the folly wall came from London Thames Gateway and the council. The following phases were funded as part of the development deal with the private developers Redrow Regeneration, in an agreement where the Council took no receipts for the land value.

Barking Town Square was instigated by the Barking Spatial Regeneration team (a department within a local authority) and commissioned as one of the Mayor’s 100 Public Spaces (an early initiative of the London-wide mayor’s office and the Richard Rogers led but now abolished Design for London department). It was funded through private development and public money as a subsidised site.

The official line perhaps gives some sense of the multiple interests which we were able to at times draw on in different ways in order to realise the scheme.

Despite this, the redevelopment underwent a false start. Urban Catalyst was the first developer – somewhat inexperienced, somewhat idealistic, they went bust and Redrow Regeneration replaced them as client. After some discussion, which we were not party to, muf were retained. This was in part because the head of the council, known as ‘leader’, liked the parti of the arboretum and open space.

During the period of detailed design and construction Redrow 1 was the client.

Upon completion of the project, ownership of the square reverted to the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham along with responsibilities for maintenance.

The history of the project outline meant that planning permission was given for the development with minimal requirements for local consultation, yet a fundamental part of the project was a public space in

the centre of the town, and so our clients were the local end users. It was at the earliest stage of the project when we first described ourselves as double agents – working for one interest in the hope of working for another. The eventual enthusiasm for the project meant that we shifted from double agents back to agents – the public realm we had designed for the people of Barking was eventually embraced by Redrow and used in their marketing materials.

We called the first muf book, published in 2001, a manual. Thinking that a book suggesting roof extensions would have the most likely readers, this title prompted a combination of autobiography and methodology, but much of it was aspiration, a methodology as proposition and intent. We are now more knowing, but weirdly enough retain something of that optimism almost as an act of aggression, holding briefs to account through (what Keller Esterling in her work calls) exaggerated compliance. What can come across as a priggish sincerity – by taking the platitudes

of shared vibrant public spaces at face value, as sincere, we continually insert what is missing – the ungovernable, the uncontrolled, the thing that is not made room for at any cost, check or risk register. Barking as a project has multiple audiences including students, lecturers, landscape and public space architects, clients and artists, so what seems important is to explain what it takes to do a project like this.

We had two initial impulses, which prompted the parti pris:

The first was to clear space in front of the town hall to make some ‘space for’ the civic, because it was the civic that seemed to under threat, confronted with the sheer scale of development that was coming up so close.

The second was to respond to the initial wind and shade analysis (a drawing in chalk done at speed for an impromptu review by Richards Rogers, see fig. 2) by filling that part of the site with trees. The drawing illustrates the following observations that we then realised in the first design moves (see fig. 4-6):

fig. 4 – 300 people working in the town hall,

150 visiting for meetings

fig. 5 – Café, 30 seats

fig. 6 – Residents

1. A route and a destination:

Pedestrian movement

We observed at our earliest visit the busy pedestrian route across the site from the Gascoigne Estate in the southwest to the Vicarage Field shopping centre and the station in the northeast. The proposed dense mix of housing and the diverse destinations of the development meant that the new square could belong to both existing and new residents. Later, when there was a loss in confidence in the value of investing in the public realm, we returned with a set of images that demonstrated the value of the public functions of health care and the town hall by showing the numbers of people who would be present in this place of the poor and disenfranchised – the doctors in the health centre, the barristers in the magistrates court the visitors to the town hall, all of whom contribute to the economics of the civic. We did this to counter the client’s anxiety around public spaces that encourage the presence of the poor and their infrastructure.

2. Informal surveillance

Informal surveillance through use and overlooking delivers a benign sense of mutual care and increased perceptions of safety, enabling both young and old to feel able to dwell and socialize in a space. The development brings a greater degree of informal surveillance due to the extended opening hours of the proposed library and the town hall, the cafes and shops and the overlooking of the flats around the square, this is an asset to be built upon and part of the argument to mitigate the client’s anxiety.

3. The spaces created by new developments

The height and close adjacencies of the new buildings create hostile ground conditions of shade and extreme down draughts of wind. The scheme attenuates these conditions and addresses the marketing literature fantasy of a square that is continually bathed in sunlight, where you can sip endless cappuccinos. We respond by filling this space with trees – layering the shade of the buildings with shade from trees.

For a year we worked closely with AHMM, architects of the buildings that surround the square. During the year that we walked the block from Central Street to their office, the figure ground changed on the site in Barking. The public realm was the means to argue certain properties for the architecture, as in the public realm ‘needs’ an active corner, so a café ‘must be placed’ there, the town centre needs to be more permeable so routes must be introduced. After a while Paul Monaghan, one of the partners, got dreamt about.

There was no requirement for consultation participation or to talk with anyone who lived in Barking or used the town centre, so the muf design team initiated an action-research dialogue with local young people to understand how they perceived and used public space. The typical response that public space was simply the meaningless bits left over between the buildings was challenged in a photographic project with these young people, where they created alternative narratives as mise-en-scenes for these spaces. These images became the site hoardings and the project was extended to

include older people in that dialogue. This aspect of the research brought accuracy to the design dialogue, where real people and their actual aspirations, ambitions and anxieties replaced the generic end user of the marketing literature.

The project required a design build contract. We had ambitions for a careful resolution of detail but did set out with a degree of realism recognising the constraints we were under. It was achieved by unevenness – large areas of simplicity, where single materials were specified, contrasted with small areas of detail. (These moments of detail often required fights, or negotiations where we had to firmly stand our ground, in order to be realised).

For example

The square: pink granite from Northern Spain and a single sentence for 30 m of specials included in the client requirements. The fight to procure this from the selected quarry eventually became enshrined as Council policy, which is to procure as locally as possible. Benches were muf-adapted rather than authored from scratch.

The folly: this was outside the contract and site with Redrow, but tied in to the project through a continuation of materials and lighting. The care and the control inherent in a traditional architects contract was expanded through a nurtured relationship with the master bricklayers, but also as a bulwark, or a reason to be entering the council offices and therefore offering other ways to tie in both projects.

The arcade: the black and white tiles are standard, as are the light fixtures. Only the chandeliers were ‘specials’. They are an enlarged version of a Tom Dixon studio lampshade adapted for external use. There was a fight: as the only element without a proven application, the warranty was eventually taken on by Barking council itself.

The arboretum: every element was standard except the cast branches, which interrupt some of the balustrades, and keep pedestrians from walking across the tree pits.

1 Redrow has since become notorious for its promo-film which mimed American Psycho.

Read article