“The first shock of a great earthquake had rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre … Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood. Everywhere were bridges that led nowhere; thoroughfares that were wholly impassable; Babel towers of chimneys, wanting half their height … wildernesses of bricks and giant forms of cranes and tripods straddling above nothing … In short the yet unfinished and unopened Railroad was in progress; and from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilisation and improvement”. (Dombey and Son Dickens 1834)

Scenes in Barking & Dagenham today resound with such moments of wholesale upheaval that Dickens described with the arrival of the railways. Today we are not just assailed by the cranes, demolitions, blocked-up passages and rights of way, but also with the import of the glaring super graphics of development hoardings that draw heavily on generic images of bland

lifestyle goals. These shy away from reflecting the complex and diverse aspirations of London and its worldly-wise citizens. The hoarding could instead give developers a real opportunity to engage with the present and future contexts using temporary enhancements of the existing and snapshots of the possible.

Barking & Dagenham is changing rapidly, with development activity growing in a seemingly exponential fashion. It is important that this period of change should not adversely affect the experience of living in and growing up in Barking. It is not only construction sites and their perimeters that can have a negative impact on an area. Sites that form part of masterplans or areas of the city that have been identified as possible development sites or places of opportunity are effectively blighted for the period of deliberation. Although there is an understandable resistance to any investment with a limited shelf life, temporary improvements can be approached in a way that limits ‘wastage’ and seen as an opportunity to test options and limit risk by trying out possible scenarios of use or design treatment.

by Katherine Clarke and Liza Fior

fig. 37 – Temporary occuptaion

fig. 38 – Hoarding documenting temporary occupation

This is an expanded account of a presentation of one project for a new public space in the very East of London, a destination for any traveller falling asleep on an eastbound Hammersmith and City Line. It is concerned with what it takes to make a space that will endure once the architect leaves the site.

Barking Town Square, by way of the UK Pavilion in Venice 2010, was used as a means to describe the tactics needed to promote the value of the public realm to those, particularly the client paying for it, who do not go to conferences or read publications such as this, and to build trust over the five years it took to complete the project. Tactics and contrivances included invitations and ways into the design process, which extended the project beyond our design team and the site itself. These tactics also necessitated a flexible understanding of who the client was: the developers funding the project or the ultimate user.

Barking Town Square was presented in the exhibition Feminist Practices 1 when only half completed, when the arboretum stage 2 of the project was only

an illustration. This text is an opportunity to theorize, if we can rely on Raymond Williams’s explanation of ‘theory’ as a ‘scheme of ideas which explain practice’ the talk which first generated this text (Vienna, November 2010) was revisited as an opportunity for further reflection 2. Although the built project for the square was completed in Spring 2010, further negotiations since then include rewriting a maintenance contract in order that a local city farm take responsibility for the everyday gardening and is on the alert for stray vodka bottles left nestling in the woodland planting after a Saturday night.

The architect acts as agent – sometimes double agent – in the realization of a brief. This is inevitable when a brief is for a public space and by a client who is wary of what that might imply.

Before the presentation proper, the talk began with the observation that it was ironic to be talking about the potential of the public realm at a time when the impact of recent cuts in public services is already apparent. You telephone a local authority client for some routine matter and discover they no longer work there; you are arguing for the priority of a built scheme over keeping a library open,

and the question is how complicit you are when you apply your skills, whether tactical or spatial, to keeping safe, shared spaces. Design cannot be separated from the wider political landscape and from discussions about what is cut, what is sold, what is precious, what can go, how hard it is to replace things once gone and finally what is of value. The presentation began with of Barking Life, a photograph taken in a moment that took 5 years to compose.

Just as Jeff Wall composes his pictures meticulously, for example installing a subject in a flat so that it is sufficiently lived in before taking the shot, this picture of children clambering over a vast semi-submerged fallen tree trunk took five years to realize. The invisible armature that made the snapshot possible is a continuous web of negotiations, small battles and tactical moves. Process and project as object are given equal status and the marginalia of making the project and making it possible are given equivalence.

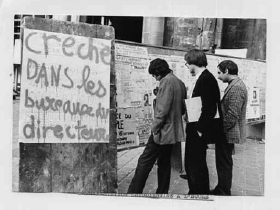

Meaning can be changed by occupation rather than typology, a point illustrated by this image from Paris ’69 (fig. 39 – the strikes continued after ’68) – we think of the Ecole des Beaux Arts – where the Director’s office has been redesignated as a crèche.

fig. 39

This renaming is a reverse form of master planning establishing strategy through detail: use is described through use.

A short description of the UK pavilion in Venice authored by muf was used as a quick introduction to both the argument and the methodology employed. The pavilion was furnished with The Stadium of Close Looking™, a 1:10 model of a section of London’s Olympic stadium, repurposed as a drawing studio flanked by examples of fragile ecologies including ephemera from the British and Italian Women’s Movement. The pavilion made room for Venetian preoc-cupations both as exhibit and meeting place. In many ways the entire six-month process

from commissioning was a preparation for the final day, the only day when people could ‘meet in architecture’ (the premise of the whole Biennale) without paying €20. Not only was the pavilion materially adjusted but there was also a continuous and repeated attempt to make it available through meetings and collaborations. The project intention was to muddy the edges of the building’s boundaries and footprint 3: for example on 21st November 2010 an event called Salutiamo Venezia was organised, in which different interested parties – including those protesting about water privatization and the selling off of hospitals as hotels – used the stadium for meetings, while at the same time children quietly but busily built large nests in the undercroft.

Barking is a place with a history, the site of a seventh century abbey, industry (fishing, boat building) and then high postwar unemployment, until it became the site of grand plans for the Thames Gateway, an extension of London with Barking as a new town centre with a new town square. Suddenly a place where there had been no

investment for 60 years was filled with cranes. In this situation the things that seemed most fragile were the ‘civic;’ the Town Hall literally overshadowed by private housing and secondly, the place of history in the midst of change.

Muf were responsible for the public realm for a commercial mixed-use development, that included street level council offices and a library, classrooms and café with housing above. The end client and landowner, to whom the square would eventually be handed over, was the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, the immediate project client was a developer of volume housing, and the architects were the successful and busy UK practice AHMM (Alford Hall Monaghan Morris)

The project was delivered in stages and each increment was an opportunity to build trust with the client for the next stage: each design move prefigured the next. Our commission was to create a town square, ‘a sunny space for new and existing communities to meet and drink coffee in the sun,’ ‘a platform for social cohesion’.

A first analysis of the site demonstrated that sunny space was actually shady

and that the height and configuration of the new buildings would draw in a southeasterly wind. This reading allowed us to make the first move to divide the site in two and make shady more shady, our understanding of public space not as an unremitting condition of cheeriness but the assertion that mystery, moodiness, and the desire to be alone have their place.

The scheme is two linked spaces: one empty, one filled. The first a hard landscape, as open ended; as a platform for use as the original construction drawings for the town hall, where moving chairs around could turn the space from a boxing ring to a dance hall. The second space we filled with trees and protected by naming it an urban arboretum. Most importantly at this early stage we were invited to make an art commission with an unusually open brief in terms of site and outcome: we secured a site at the west end of the proposed square which rendered the L-shaped site a T, a bastion from which we could operate more independently.

The intuitive first reading of the limitations and opportunities of the site was combined with weekly meetings with the architects. The footprints of the buildings and the spaces between them registered the

building up of trust and one building became two. Pedestrian routes, as rights of way, made their way through the site.

Phase 1: Years 2-3

The first 2 and 3 phase years delivered two wildly contrasting pieces of the final square. One intentionally self effacing with little to argue about, the second complex in its making.

The area in front of the Town Hall was paved in pink Spanish granite. That was it, apart from long timber benches painted in the palest of pink, deliberately sacrificial ready to register the vandalism that was predicted. What happened? People simply sat on them, and anxiety concerning the inappropriate behaviour that the provision of public space might provoke was addressed. The role of the civic was celebrated in oversized terrazzo paving and urban chandeliers (designed with Tom Dixon) that made a route between shopping street and Town Hall.

The art commission was under way. A folly, its provenance was very different to the rest of the square. It was as much about its procurement and making as its role formally. Formally this 7-m high folly not only makes the L-shaped site of the original

brief into a T but masks the back of a supermarket in an adjoining street by introducing a new façade which is only one brick thick. It can be read as a memento mori facing the new architecture of the new Barking, incomplete and alluding to a lost history for the site. This instant ruin is a composition of architectural salvage, built drawing on the expertise of the master bricklayers of Barking College 5. The art commission was not on the site controlled by the developer, but adjacent to it, though all seemed to belong to a single whole. The main contractors were both amused and supportive of the traditional building techniques just next to the main site. Once unveiled the folly allowed us to introduce detail in the making of the next phase and was a model for the role of the bucolic, the open ended, a container for some things lost.

The two parts of the new square, open hard-landscaped ‘room’ and arboretum, are conjoined with a set of steps (exact copies in form and scale of the steps to the Town Hall) which extend as a stage, with power, water and internet access. In advance of delivering the next phase, we substituted the generic developer’s publicity hoarding (construction fencing)

with a 1:1 model of these steps backed by an image of woodland, a hoarding that you could sit in, where again the ‘what might happen’ with the introduction of informal seating was demonstrated by use, co-opted as stage and photo-opportunity as much as for lounging.

By now many arguments had been won, including the new public space recognized as a space for events and gatherings, both formal and informal, the possibilities of mixing detail and background, the bespoke and the generic, the place of art practice all within a culture of the design-build project where limiting risk is so high a priority and design is considered the highest risk of all.

The arboretum is a series of micro woodland ecologies. Glades of multistem birch trees with forest floor planting are interspersed by other set pieces; cherry trees are placed around the stage with swamp cypresses deeper into the plan. The arboretum combines nature and artifice, the low walls to mitigate the wind from the surrounding building are cast in shuttering impressed with a tree bark pattern usually seen in German car parks of the 1970s, and indulged forays to Epping Forest to select branches cast as the balustrade uprights.

The benches tested in phase 1 went through multiple transformations, stretching around to protect planting, somewhere for two people to sit at the end of a tiled promontory. The arboretum is adjacent to the library. Different overtures were made to the librarians, one of which was a collaboration with a writer and product design students from the Royal College of Art who made library furniture both for inside and outside as temporary furnishings. Two of the students’ pieces were made permanent. Again, the collaboration was a means to pursue ideas outside the main contract and programmed.

The client had by this time, conceded so many of their reservations and the public realm, which had seemed a hindrance to selling flats, was by now being featured on the sales brochure. All that remained was the inclusion for play. Stealth play had been previously included: the stage was being used for performances, the square was both a site for special events, summer beach volleyball, and winter temporary ice rink. However, we kept play until the very last phase for year 5. Anxiety about the implications of what the public realm might bring to land values was heightened when it came

to the presence of the child. Is not the act of agency in the architectural process the means to represent those not included in the client team, for example the child?

The tactical moves to include play were a form of play in itself, appropriating the structures of the building contract and the commission, to find uses outside bald descriptions of hard and soft landscaping, wind mitigation and seating. The final proposals intentionally were not conventional play equipment. Vast tree trunks are partially sunk in the ground high enough to require safety surface, somewhere for the urban child to experience some pleasures of a forest which would require another hundred years before this arboretum got there.

The client, recognizing the pleasures of his childhood, agreed to it at first glance.

by Katherine Clarke and Liza Fior

1 To see the Feminist Practices website click here.

2 Raymond Williams, Keywords (London: Croom Helm, 1976) p. 316

3 For examples of muddied edges see the Villa Frankenstein website by clicking here, and to read more about the Thames Gateway project click here.

4 To find out more about AHMM click here.

5 To find out more about bricklaying at Barking College click here.