Barking is part of the Borough of Barking and Dagenham in Greater London, situated to the east of the city at the very end of the District and Hammersmith and City line. In 2004 we went on our first muf site visit – to a carpark for Barking’s town hall. This strange place read as a back land, standing as it did to the rear of shops, with flats above, which included a funeral parlour with its horses, and a fish shop that stood where the arcade now stands, which had a black and white tiled floor. This is echoed in the floor of the new arcade, and many of our projects have these memorial qualities, like an archaeology of the unimportant world – celebrating the fragile can have these repercussions.

The public space now called Barking Town Square sits in front of the town hall, where this carpark once was, and occupies the spaces between the new buildings of the town centre development. It was built in four stages between 2006 and 2010, and muf continued to work on satellite projects in Barking’s town centre until 2013. The town square is a T-shaped space of 6000 m², and is composed of four overlapping elements:

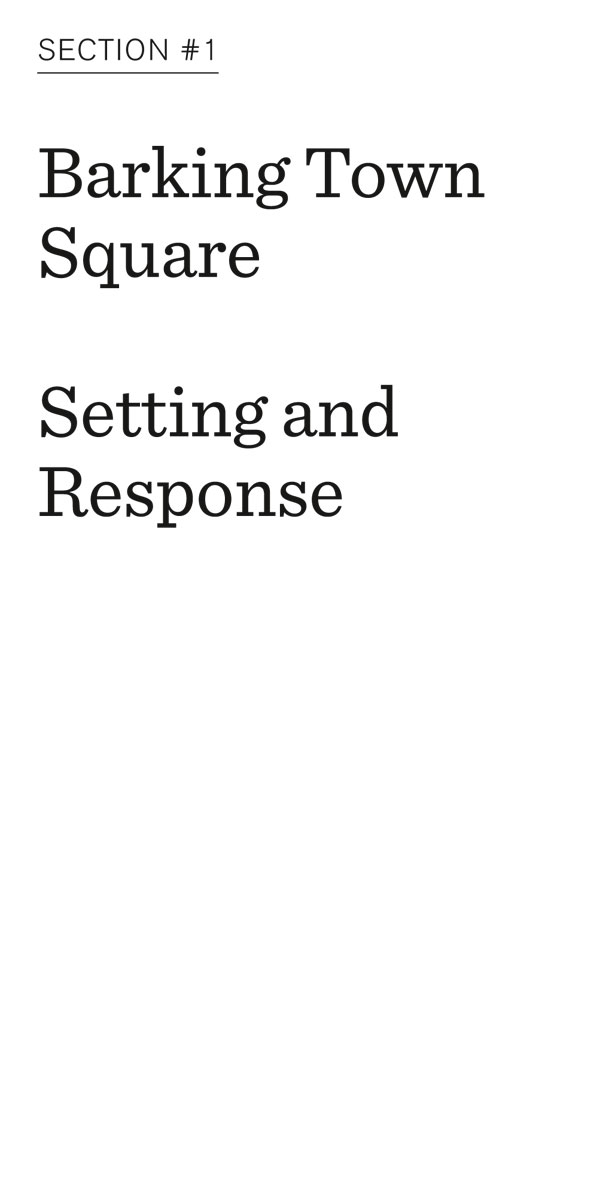

the civic square, the arboretum, the folly wall, and the arcade, each of which is described in the Catalogue of Parts. (see fig. 1 for location). The phases in which it was built did not correspond to these discreet elements, however, and each phase of the public realm was dependent on and a requirement of the private housing, one triggering the other. The delivery of the square was part of the initial phase of a larger redevelopment masterplan to provide high to medium density housing of approximately 500 new homes, a newly-built library, a one-stop shop providing community support, a children’s and primary health centre, accommodation for

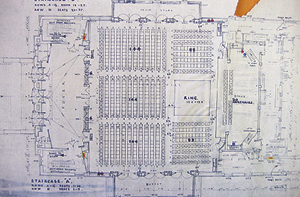

fig. 1 – Site plan

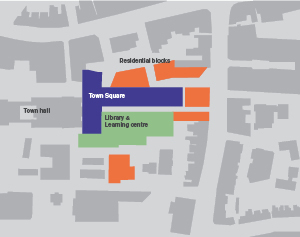

fig. 2 – A route and a destination: this plan shows the shade and airflow inbetween the new buildings.

fig. 3 – View to AHMM’s residential block

over library phase 1

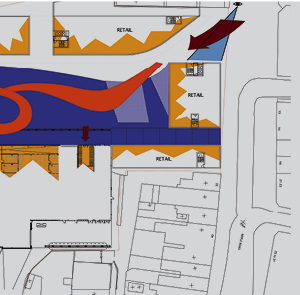

fig. 4 – Timeline

the University of East London, a hotel, shops and cafes. (fig. 3 shows phase 1 of the masterplan, Allford Hall Monaghan Morris Architects – AHMM’s residential block over the library, under construction.)

Having had no private investment for 60 years, funding for the redevelopment came all at once: masterplans were made and we were able to contribute to the wider planning through the square. This acted as exemplar both as the space itself, but also as an illustration of principles (which is partly recorded in the Barking Code). Funding for phase 1 and the folly wall came from London Thames Gateway and the council. The following phases were funded as part of the development deal with the private developers Redrow Regeneration, in an agreement where the Council took no receipts for the land value.

Barking Town Square was instigated by the Barking Spatial Regeneration team (a department within a local authority) and commissioned as one of the Mayor’s 100 Public Spaces (an early initiative of the London-wide mayor’s office and the Richard Rogers led but now abolished Design for London department). It was funded through private development and public money as a subsidised site.

The official line perhaps gives some sense of the multiple interests which we were able to at times draw on in different ways in order to realise the scheme.

Despite this, the redevelopment underwent a false start. Urban Catalyst was the first developer – somewhat inexperienced, somewhat idealistic, they went bust and Redrow Regeneration replaced them as client. After some discussion, which we were not party to, muf were retained. This was in part because the head of the council, known as ‘leader’, liked the parti of the arboretum and open space.

During the period of detailed design and construction Redrow 1 was the client.

Upon completion of the project, ownership of the square reverted to the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham along with responsibilities for maintenance.

The history of the project outline meant that planning permission was given for the development with minimal requirements for local consultation, yet a fundamental part of the project was a public space in

the centre of the town, and so our clients were the local end users. It was at the earliest stage of the project when we first described ourselves as double agents – working for one interest in the hope of working for another. The eventual enthusiasm for the project meant that we shifted from double agents back to agents – the public realm we had designed for the people of Barking was eventually embraced by Redrow and used in their marketing materials.

We called the first muf book, published in 2001, a manual. Thinking that a book suggesting roof extensions would have the most likely readers, this title prompted a combination of autobiography and methodology, but much of it was aspiration, a methodology as proposition and intent. We are now more knowing, but weirdly enough retain something of that optimism almost as an act of aggression, holding briefs to account through (what Keller Esterling in her work calls) exaggerated compliance. What can come across as a priggish sincerity – by taking the platitudes

of shared vibrant public spaces at face value, as sincere, we continually insert what is missing – the ungovernable, the uncontrolled, the thing that is not made room for at any cost, check or risk register. Barking as a project has multiple audiences including students, lecturers, landscape and public space architects, clients and artists, so what seems important is to explain what it takes to do a project like this.

We had two initial impulses, which prompted the parti pris:

The first was to clear space in front of the town hall to make some ‘space for’ the civic, because it was the civic that seemed to under threat, confronted with the sheer scale of development that was coming up so close.

The second was to respond to the initial wind and shade analysis (a drawing in chalk done at speed for an impromptu review by Richards Rogers, see fig. 2) by filling that part of the site with trees. The drawing illustrates the following observations that we then realised in the first design moves (see fig. 4-6):

fig. 4 – 300 people working in the town hall,

150 visiting for meetings

fig. 5 – Café, 30 seats

fig. 6 – Residents

1. A route and a destination:

Pedestrian movement

We observed at our earliest visit the busy pedestrian route across the site from the Gascoigne Estate in the southwest to the Vicarage Field shopping centre and the station in the northeast. The proposed dense mix of housing and the diverse destinations of the development meant that the new square could belong to both existing and new residents. Later, when there was a loss in confidence in the value of investing in the public realm, we returned with a set of images that demonstrated the value of the public functions of health care and the town hall by showing the numbers of people who would be present in this place of the poor and disenfranchised – the doctors in the health centre, the barristers in the magistrates court the visitors to the town hall, all of whom contribute to the economics of the civic. We did this to counter the client’s anxiety around public spaces that encourage the presence of the poor and their infrastructure.

2. Informal surveillance

Informal surveillance through use and overlooking delivers a benign sense of mutual care and increased perceptions of safety, enabling both young and old to feel able to dwell and socialize in a space. The development brings a greater degree of informal surveillance due to the extended opening hours of the proposed library and the town hall, the cafes and shops and the overlooking of the flats around the square, this is an asset to be built upon and part of the argument to mitigate the client’s anxiety.

3. The spaces created by new developments

The height and close adjacencies of the new buildings create hostile ground conditions of shade and extreme down draughts of wind. The scheme attenuates these conditions and addresses the marketing literature fantasy of a square that is continually bathed in sunlight, where you can sip endless cappuccinos. We respond by filling this space with trees – layering the shade of the buildings with shade from trees.

For a year we worked closely with AHMM, architects of the buildings that surround the square. During the year that we walked the block from Central Street to their office, the figure ground changed on the site in Barking. The public realm was the means to argue certain properties for the architecture, as in the public realm ‘needs’ an active corner, so a café ‘must be placed’ there, the town centre needs to be more permeable so routes must be introduced. After a while Paul Monaghan, one of the partners, got dreamt about.

There was no requirement for consultation participation or to talk with anyone who lived in Barking or used the town centre, so the muf design team initiated an action-research dialogue with local young people to understand how they perceived and used public space. The typical response that public space was simply the meaningless bits left over between the buildings was challenged in a photographic project with these young people, where they created alternative narratives as mise-en-scenes for these spaces. These images became the site hoardings and the project was extended to

include older people in that dialogue. This aspect of the research brought accuracy to the design dialogue, where real people and their actual aspirations, ambitions and anxieties replaced the generic end user of the marketing literature.

The project required a design build contract. We had ambitions for a careful resolution of detail but did set out with a degree of realism recognising the constraints we were under. It was achieved by unevenness – large areas of simplicity, where single materials were specified, contrasted with small areas of detail. (These moments of detail often required fights, or negotiations where we had to firmly stand our ground, in order to be realised).

For example

The square: pink granite from Northern Spain and a single sentence for 30 m of specials included in the client requirements. The fight to procure this from the selected quarry eventually became enshrined as Council policy, which is to procure as locally as possible. Benches were muf-adapted rather than authored from scratch.

The folly: this was outside the contract and site with Redrow, but tied in to the project through a continuation of materials and lighting. The care and the control inherent in a traditional architects contract was expanded through a nurtured relationship with the master bricklayers, but also as a bulwark, or a reason to be entering the council offices and therefore offering other ways to tie in both projects.

The arcade: the black and white tiles are standard, as are the light fixtures. Only the chandeliers were ‘specials’. They are an enlarged version of a Tom Dixon studio lampshade adapted for external use. There was a fight: as the only element without a proven application, the warranty was eventually taken on by Barking council itself.

The arboretum: every element was standard except the cast branches, which interrupt some of the balustrades, and keep pedestrians from walking across the tree pits.

1 Redrow has since become notorious for its promo-film which mimed American Psycho.

Read article

The design code covers the whole town centre of Barking and sets out the material palette and generic details at the scale of the macro, from raised tables and radius kerb edges to the micro, the joints between materials. The code is the council’s tool for subsequent design guidance and

maintenance to ensure there is a continuity and coherence of design. The code highlights the tension in much of muf’s work between the bespoke designed for the specific and the desire of the client for a general solution that can be applied to any situation – the Strategy (s) element of Kath Shonfield’s muf equation: d/s=D, but without the resolution in D.

fig. 7 – Site plan

The square in front of the town hall is conceived as a huge outdoor room scaled to the larger-than-life dimensions of the civic, dense with the largesse of possibilities and inspired by archival drawings of the town hall that illustrate the spatial flexibility when chairs are rearranged (see fig. 8) – from debating chamber to transform into a wrestling ring or theatre. In contrast to the density of objects in the arboretum, the civic square is conceived as an empty room, a flexible space that can be programmed for activities generated by the institutions that flank it and other one-off events.

The paving consists of 200 mm strips of flamed pink Spanish granite in random lengths; larger pieces of granite mark the threshold to the new library building. The granite paving is extended to the north across a public access road to enlarge the square, making it a T-shape in plan, rather than an L. The pink hue of the flamed Spanish granite mediates between the red brick of the town hall facade and the shiny white new library and contrasts with the grey granite used elsewhere in Barking.

fig. 8 – Plan of the Town Hall, showing the

Council Chamber set out for a wrestling match

fig. 9 – muf argued on ethical grounds against procuring Chinese granite for reasons of carbon footprint and controversial labour practices. This proposal was embraced by Barking and has now become policy.

fig. 10 – The Civic square

fig. 11 – The Civic square

fig. 12 – Town hall steps

fig. 13– Steps to the arboretum

LBBD were lobbied by the Asbestos Victim Support Group of Barking Dagenham to have a memorial installed in the square. Since the only thing that alleviates asbestos poisoning is water, muf proposed a bespoke memorial drinking fountain in the form of a tree trunk carved from Portland stone. The water fountain is an extension of the arboretum. It makes a spatial connection to the folly wall and constitutes a transition between the two. It was erected with support from The Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association.

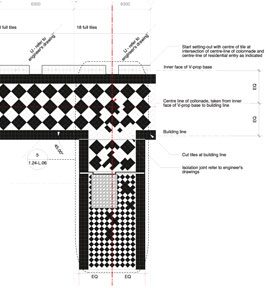

The colonnade as the route from the town hall steps to Ripple Road, Barking’s main shopping street, was established through a design dialogue with the architects AHMM where muf proposed pulling back the façade of the two lowest floors of the library building to make a covered route.

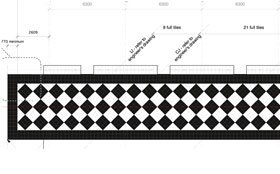

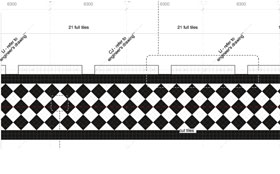

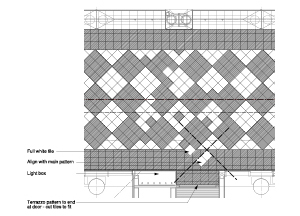

This 80-m long, and 8-m high route is enclosed and separated from the arboretum by diagonal columns and is paved with black and white terrazzo tiles. Standard black and white 300 mm square paving tiles are grouped in diamonds each composed of 9 tiles. The pattern and layout of the terrazzo makes a ‘welcome mat’ out into Ripple Road and the regular diamond pattern inflects to mark the entrances to the private flats above, the public amenities of the library and the one-stop-shop, giving them equal status.

The terrazzo paving tiles refer to the grandeur of urban arcades and to the paths leading up to London’s Edwardian villas,

so even the prosaic act of renewing a parking permit becomes a ceremonial activity.

The arcade is lit by 13 large golden chandeliers, which fill the lofty space with light and suggest the glamour of a ballroom. They were designed in collaboration with British product designer Tom Dixon and electronics company Philips. They area hybrid design made for an interior fitting by Hiroki Takada, which has been magnified by 3 and adapted to its external location. The scale and scale of the floor tiles bring down the sense of the height of the roof.

fig. 14 – Finished arcade

fig. 15 – Set out of terrazzo flooring

fig. 16 – Terrazzo detail

fig. 17 – The folly wall encloses the

civic square on its north side

fig. 18 – The folly wall is designed as a reference to the ruins of the former royal monastery at Barking Abbey.

The folly wall was the result of an art commission to muf with an initial brief to work as artists on the design team with the architects Burns and Nice who were designing Clockhouse Avenue, the road leading up to the town square. muf expanded this brief as an opportunity to extend the design dialogue already initiated through the design of the town square.

The site on Clockhouse Avenue was one of the locations for the initial action research performance with the young people. From this activity, the construction of an alternative fantasy, muf conceived the wall. The wall is prosaic, it masks the back of house and service yard to the Iceland supermarket, it is strategic, it enlarges and creates the fourth elevation to the civic square and provides somewhere to sit in the sun and it is intentionally poetic.

The folly wall was designed as a ruin to refind what Barking was losing, a sense of its past, the wall references Barking Abbey and nearby Eastbury Manor and is composed of architectural salvage embedded in a brick thin skin that evokes not the truth of

its existence but recovers the texture of a lost historic fabric and stands as a memento mori to this current cycle of regeneration. In contrast to the homogenized visual environment of the factory made façade-panel skins of the new buildings surrounding the town square, the wall is entirely hand made, and was conceived as a means to recover construction skills that successive cycles of regeneration have eroded.

The detail design was established through test building with the local apprentice bricklayers and their masters at Barking College. A number of apprentices were taken on during the construction and the design continued as collaboration with bricklayer construction team – Shane, Steve, John and Arran from Excell Brickworks.

The build began with a visit to the Soane Museum with the Bricklayers for an archive tour of Soane’s documentation of the building of the Bank of England (Soane’s father was a bricklayer) The bricklayer’s inherent skills and experience of the limits and possibilities of the process transformed the collection of reclaimed pieces into a coherent whole.

The response of passers-by to the wall was documented by muf while on site during the build, people expressed a persistent belief that the wall had always been there, or had been reconstructed as a renovation from another site in the borough. The invisible support structure for the wall was achieved physically through engineering, and metaphorically through project management. Atelier One engineered the steel structure and method by which the brick skin is pinned to give it lateral stability. Peter Watson, the borough engineer, project managed, nurtured, inspired and protected the unconventional design and build process with the bricklayers.

Soane’s father was a bricklayer, so we took the bricklayers to the Soane Museum in a stretch limo – it was a very weird journey. Collaborating artist Verity Keefe and I went too – stretch limos are very seedy and that was the first time we had met the bricklayers. As we drove through London they pointed out the things they had built, conscious that brick laying was being replaced by prefabricated brick skins. The curator of the Soane Museum gave them a guided tour and then showed them drawings and paintings of bricklayers building the Bank of England. It was a way to give real weight to their skill and set them up with a sense of their creativity and craft in what they were doing.

fig. 19 – Architectural salvage

fig. 20 – Architectural salvage built into the wall

fig. 21 – Architectural salvage built into the wall

The arboretum derives from an image of nature as an escape and as otherworldly. It takes as its model the enchanted forest of Midsummer’s Nights Dream or Dear Brutus, where it is a site of liminality and transformation. It mirrors in depth the original council buildings its line of symmetry the steps.

Traditionally, an arboretum is a curated collection of specimen trees according to a specific theme. In Barking, the collection consists of 40 mature trees of 13 different species arranged to create settings of different scales and character. Key trees are selected in reference to texts held in the new library and make direct links to fictional situations in literature suggests a simultaneity of fiction and reality that is also present in the folly wall.

The tree species and varieties are as follows; where the arboretum meets the civic square cherry varieties create a year-round, white-flowering backdrop, with the arrangement of the trees forming a proscenium around the stage. The adjacent cluster is made up of pendulous swamp cypresses planted in and around an undulating

play structure, which has a dramatic intense orange-red autumn colour. Between these more formalized settings, are woodland ecologies of native multi-stemmed trees. These are planted with ground cover including translocated seeds from local ecologies such as Epping to give random accents.

Key desire lines criss-cross the space and between them the ground undulates, falling to create damp woodland ecologies and rising to create more formalized stages and promontories into the wooded areas. The arboretum embodies a potential for play (and recognizes adults and children as equal participants). Play is not ring-fenced but fostered through such devices as the miniaturization of street furniture, the transgression of boundaries to create intimate spaces, and high artifice, whereby casts of tree branches and of stacked tree trunks form balustrades and walls. The balustrades and cast log walls have references to Florentine details, such as the rails holding the tourists in the Piazza Della Signora at arms length, and the cast logs in the Barboli gardens which casually edge the paths.

The literary references are formalized in the outside reading room created by the

stage/steps that exactly mirror the steps leading up to the town hall and which link the arboretum to the adjacent Library and to the University of East London outpost. The decision to mirror the steps reflects an ambition to reconnect people, if only subliminally, to the political and social construction of democracy. The spaces beyond the stage mirror the town hall, as the scale of the arboretum is almost equivalent to that of its civic interior, its line of symmetry the steps (an exact surveyed ‘model’ of those at the entrance to the town hall).

The lighting is designed to accentuate the ephemeral quality of the trees. It has seasonal settings that respond to the changes in the colour of the trees and is directed through the canopies to create layered and shifting shadows on the ground. The same chandeliers are used as in the arcade, but here they reflect light rather than emit it.

The trees in the arboretum have come together as if from the Victorian Park, and this explicitly celebrates everyday specialness and luxury. But these parks were made for Sundays, the arboretum replays the proximity of the Georgian square – Royal Avenue moves east.

fig. 22 — The arboretum with its mature trees occupies the shadow space between the new buildings.

fig. 23 – Large tree trunks for play

fig. 24 – Arboretum, stage and town hall

fig. 25 – Arboretum, stage and town hall

fig. 26 – The planting pits are sunken and enclosed

fig. 27 – Desire lines criss-cross the arboretum. The golden chandelier from the arcade is used also in the arboretum.

fig. 28 – The paving from the arcade is extended

into the arboretum

fig. 29 – Concrete tree trunk walls

fig. 30 – Cast branches

fig. 31 – Trees

Alnus glutinosa

Winter Alder

Betula nigra

River Birch

Prunus Avium

Wild cherry

Robinia Pseudoacacia

False Acacia

Betula Jaquemonti

Himalayan birch

Populus Tremula

Quaking aspen

Quercus Robur

Pin oak

Taxodium ascendens nuttans

Swamp cypress

Prunus Autumnalis

Winter flowering cherry

Prunus Serula

Tibetan cherry

Juglans Regia

Walnut Tree

Salix tristis

Willow

The Barking bench is a muf adaptation of a standard manufacturer’s product. The colour and the design of each bench is always specific to the location, for example, outside the health centre the bench has a stool for elevating and resting a leg, there are benches miniaturized to the scale of the child and benches that are extended in length to make more generous seating. This family of benches is part of the Barking code, and bespoke benches are situated outside the station and in the Short Blue Place Square.

fig. 32 – Arboretum bench

fig. 33 – Pink bench

fig. 34 – Extended bench

fig. 35 – Round bench

fig. 36 – Bench with table

fig. 37 – Station parade, Barking

“The first shock of a great earthquake had rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre … Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood. Everywhere were bridges that led nowhere; thoroughfares that were wholly impassable; Babel towers of chimneys, wanting half their height … wildernesses of bricks and giant forms of cranes and tripods straddling above nothing … In short the yet unfinished and unopened Railroad was in progress; and from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilisation and improvement”. (Dombey and Son Dickens 1834)

Scenes in Barking & Dagenham today resound with such moments of wholesale upheaval that Dickens described with the arrival of the railways. Today we are not just assailed by the cranes, demolitions, blocked-up passages and rights of way, but also with the import of the glaring super graphics of development hoardings that draw heavily on generic images of bland

lifestyle goals. These shy away from reflecting the complex and diverse aspirations of London and its worldly-wise citizens. The hoarding could instead give developers a real opportunity to engage with the present and future contexts using temporary enhancements of the existing and snapshots of the possible.

Barking & Dagenham is changing rapidly, with development activity growing in a seemingly exponential fashion. It is important that this period of change should not adversely affect the experience of living in and growing up in Barking. It is not only construction sites and their perimeters that can have a negative impact on an area. Sites that form part of masterplans or areas of the city that have been identified as possible development sites or places of opportunity are effectively blighted for the period of deliberation. Although there is an understandable resistance to any investment with a limited shelf life, temporary improvements can be approached in a way that limits ‘wastage’ and seen as an opportunity to test options and limit risk by trying out possible scenarios of use or design treatment.

by Katherine Clarke and Liza Fior

fig. 37 – Temporary occuptaion

fig. 38 – Hoarding documenting temporary occupation

This is an expanded account of a presentation of one project for a new public space in the very East of London, a destination for any traveller falling asleep on an eastbound Hammersmith and City Line. It is concerned with what it takes to make a space that will endure once the architect leaves the site.

Barking Town Square, by way of the UK Pavilion in Venice 2010, was used as a means to describe the tactics needed to promote the value of the public realm to those, particularly the client paying for it, who do not go to conferences or read publications such as this, and to build trust over the five years it took to complete the project. Tactics and contrivances included invitations and ways into the design process, which extended the project beyond our design team and the site itself. These tactics also necessitated a flexible understanding of who the client was: the developers funding the project or the ultimate user.

Barking Town Square was presented in the exhibition Feminist Practices 1 when only half completed, when the arboretum stage 2 of the project was only

an illustration. This text is an opportunity to theorize, if we can rely on Raymond Williams’s explanation of ‘theory’ as a ‘scheme of ideas which explain practice’ the talk which first generated this text (Vienna, November 2010) was revisited as an opportunity for further reflection 2. Although the built project for the square was completed in Spring 2010, further negotiations since then include rewriting a maintenance contract in order that a local city farm take responsibility for the everyday gardening and is on the alert for stray vodka bottles left nestling in the woodland planting after a Saturday night.

The architect acts as agent – sometimes double agent – in the realization of a brief. This is inevitable when a brief is for a public space and by a client who is wary of what that might imply.

Before the presentation proper, the talk began with the observation that it was ironic to be talking about the potential of the public realm at a time when the impact of recent cuts in public services is already apparent. You telephone a local authority client for some routine matter and discover they no longer work there; you are arguing for the priority of a built scheme over keeping a library open,

and the question is how complicit you are when you apply your skills, whether tactical or spatial, to keeping safe, shared spaces. Design cannot be separated from the wider political landscape and from discussions about what is cut, what is sold, what is precious, what can go, how hard it is to replace things once gone and finally what is of value. The presentation began with of Barking Life, a photograph taken in a moment that took 5 years to compose.

Just as Jeff Wall composes his pictures meticulously, for example installing a subject in a flat so that it is sufficiently lived in before taking the shot, this picture of children clambering over a vast semi-submerged fallen tree trunk took five years to realize. The invisible armature that made the snapshot possible is a continuous web of negotiations, small battles and tactical moves. Process and project as object are given equal status and the marginalia of making the project and making it possible are given equivalence.

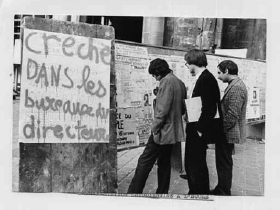

Meaning can be changed by occupation rather than typology, a point illustrated by this image from Paris ’69 (fig. 39 – the strikes continued after ’68) – we think of the Ecole des Beaux Arts – where the Director’s office has been redesignated as a crèche.

fig. 39

This renaming is a reverse form of master planning establishing strategy through detail: use is described through use.

A short description of the UK pavilion in Venice authored by muf was used as a quick introduction to both the argument and the methodology employed. The pavilion was furnished with The Stadium of Close Looking™, a 1:10 model of a section of London’s Olympic stadium, repurposed as a drawing studio flanked by examples of fragile ecologies including ephemera from the British and Italian Women’s Movement. The pavilion made room for Venetian preoc-cupations both as exhibit and meeting place. In many ways the entire six-month process

from commissioning was a preparation for the final day, the only day when people could ‘meet in architecture’ (the premise of the whole Biennale) without paying €20. Not only was the pavilion materially adjusted but there was also a continuous and repeated attempt to make it available through meetings and collaborations. The project intention was to muddy the edges of the building’s boundaries and footprint 3: for example on 21st November 2010 an event called Salutiamo Venezia was organised, in which different interested parties – including those protesting about water privatization and the selling off of hospitals as hotels – used the stadium for meetings, while at the same time children quietly but busily built large nests in the undercroft.

Barking is a place with a history, the site of a seventh century abbey, industry (fishing, boat building) and then high postwar unemployment, until it became the site of grand plans for the Thames Gateway, an extension of London with Barking as a new town centre with a new town square. Suddenly a place where there had been no

investment for 60 years was filled with cranes. In this situation the things that seemed most fragile were the ‘civic;’ the Town Hall literally overshadowed by private housing and secondly, the place of history in the midst of change.

Muf were responsible for the public realm for a commercial mixed-use development, that included street level council offices and a library, classrooms and café with housing above. The end client and landowner, to whom the square would eventually be handed over, was the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, the immediate project client was a developer of volume housing, and the architects were the successful and busy UK practice AHMM (Alford Hall Monaghan Morris)

The project was delivered in stages and each increment was an opportunity to build trust with the client for the next stage: each design move prefigured the next. Our commission was to create a town square, ‘a sunny space for new and existing communities to meet and drink coffee in the sun,’ ‘a platform for social cohesion’.

A first analysis of the site demonstrated that sunny space was actually shady

and that the height and configuration of the new buildings would draw in a southeasterly wind. This reading allowed us to make the first move to divide the site in two and make shady more shady, our understanding of public space not as an unremitting condition of cheeriness but the assertion that mystery, moodiness, and the desire to be alone have their place.

The scheme is two linked spaces: one empty, one filled. The first a hard landscape, as open ended; as a platform for use as the original construction drawings for the town hall, where moving chairs around could turn the space from a boxing ring to a dance hall. The second space we filled with trees and protected by naming it an urban arboretum. Most importantly at this early stage we were invited to make an art commission with an unusually open brief in terms of site and outcome: we secured a site at the west end of the proposed square which rendered the L-shaped site a T, a bastion from which we could operate more independently.

The intuitive first reading of the limitations and opportunities of the site was combined with weekly meetings with the architects. The footprints of the buildings and the spaces between them registered the

building up of trust and one building became two. Pedestrian routes, as rights of way, made their way through the site.

Phase 1: Years 2-3

The first 2 and 3 phase years delivered two wildly contrasting pieces of the final square. One intentionally self effacing with little to argue about, the second complex in its making.

The area in front of the Town Hall was paved in pink Spanish granite. That was it, apart from long timber benches painted in the palest of pink, deliberately sacrificial ready to register the vandalism that was predicted. What happened? People simply sat on them, and anxiety concerning the inappropriate behaviour that the provision of public space might provoke was addressed. The role of the civic was celebrated in oversized terrazzo paving and urban chandeliers (designed with Tom Dixon) that made a route between shopping street and Town Hall.

The art commission was under way. A folly, its provenance was very different to the rest of the square. It was as much about its procurement and making as its role formally. Formally this 7-m high folly not only makes the L-shaped site of the original

brief into a T but masks the back of a supermarket in an adjoining street by introducing a new façade which is only one brick thick. It can be read as a memento mori facing the new architecture of the new Barking, incomplete and alluding to a lost history for the site. This instant ruin is a composition of architectural salvage, built drawing on the expertise of the master bricklayers of Barking College 5. The art commission was not on the site controlled by the developer, but adjacent to it, though all seemed to belong to a single whole. The main contractors were both amused and supportive of the traditional building techniques just next to the main site. Once unveiled the folly allowed us to introduce detail in the making of the next phase and was a model for the role of the bucolic, the open ended, a container for some things lost.

The two parts of the new square, open hard-landscaped ‘room’ and arboretum, are conjoined with a set of steps (exact copies in form and scale of the steps to the Town Hall) which extend as a stage, with power, water and internet access. In advance of delivering the next phase, we substituted the generic developer’s publicity hoarding (construction fencing)

with a 1:1 model of these steps backed by an image of woodland, a hoarding that you could sit in, where again the ‘what might happen’ with the introduction of informal seating was demonstrated by use, co-opted as stage and photo-opportunity as much as for lounging.

By now many arguments had been won, including the new public space recognized as a space for events and gatherings, both formal and informal, the possibilities of mixing detail and background, the bespoke and the generic, the place of art practice all within a culture of the design-build project where limiting risk is so high a priority and design is considered the highest risk of all.

The arboretum is a series of micro woodland ecologies. Glades of multistem birch trees with forest floor planting are interspersed by other set pieces; cherry trees are placed around the stage with swamp cypresses deeper into the plan. The arboretum combines nature and artifice, the low walls to mitigate the wind from the surrounding building are cast in shuttering impressed with a tree bark pattern usually seen in German car parks of the 1970s, and indulged forays to Epping Forest to select branches cast as the balustrade uprights.

The benches tested in phase 1 went through multiple transformations, stretching around to protect planting, somewhere for two people to sit at the end of a tiled promontory. The arboretum is adjacent to the library. Different overtures were made to the librarians, one of which was a collaboration with a writer and product design students from the Royal College of Art who made library furniture both for inside and outside as temporary furnishings. Two of the students’ pieces were made permanent. Again, the collaboration was a means to pursue ideas outside the main contract and programmed.

The client had by this time, conceded so many of their reservations and the public realm, which had seemed a hindrance to selling flats, was by now being featured on the sales brochure. All that remained was the inclusion for play. Stealth play had been previously included: the stage was being used for performances, the square was both a site for special events, summer beach volleyball, and winter temporary ice rink. However, we kept play until the very last phase for year 5. Anxiety about the implications of what the public realm might bring to land values was heightened when it came

to the presence of the child. Is not the act of agency in the architectural process the means to represent those not included in the client team, for example the child?

The tactical moves to include play were a form of play in itself, appropriating the structures of the building contract and the commission, to find uses outside bald descriptions of hard and soft landscaping, wind mitigation and seating. The final proposals intentionally were not conventional play equipment. Vast tree trunks are partially sunk in the ground high enough to require safety surface, somewhere for the urban child to experience some pleasures of a forest which would require another hundred years before this arboretum got there.

The client, recognizing the pleasures of his childhood, agreed to it at first glance.

by Katherine Clarke and Liza Fior

1 To see the Feminist Practices website click here.

2 Raymond Williams, Keywords (London: Croom Helm, 1976) p. 316

3 For examples of muddied edges see the Villa Frankenstein website by clicking here, and to read more about the Thames Gateway project click here.

4 To find out more about AHMM click here.

5 To find out more about bricklaying at Barking College click here.

Awards

Showcased by Cabe as a model of inclusive design and exhibited at Somerset House as part of the Mayor's 100 public spaces exhibition

Winner of the European Prize

for Urban Space 2008

Nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Award, 2008

muf Team

Katherine Clarke, Liza Fior, Alison Crawshaw, Mark Lemanski, Sarah Whiting

Time Frame

The square was commissioned in January 2005 and delivered in 3 phases.

Phase 1:

Completed September 2007

Phase 2:

Completion August 2009

Phase 2:

Completion December 2010

Budget

£2 million plus £3,00,000 for commissions outside the main contract

Client

Redrow Regeneration Ltd on behalf of the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham

Contractor

Ardmore Construction ltd

Contract types

Phase 1: JCT 1998 Standard Form of Building Contract with Contractors Design

(JCT98wCD) plus amendments

Phase 2: JCT 2005 Design Build Contract (DB05) including revision 1: 2007 plus Amendments

Consultants

Barking Town Square public realm was delivered through a number of separate

contracts, each with an independent team of consultants. muf worked with these

simultaneously in different roles.

Permanent Art Commission (Phase 1):

Designer, muf architecture/art LLP

(lead consultant)

Structural engineer: Atelier One

Phase 1 Public Realm:

Architects of the public realm:

muf architecture/art LLP (lead consultant)

Architects of the adjacent buildings: AHMM

Services engineer: Atelier Ten

Structural and civil engineers: Buro Happold

Phase 2 Public Realm:

Architects of the public realm:

muf architecture/art LLP

Architects of the adjacent buildings, AHMM (lead consultant)

QS: DBK

Structural and civils engineer:

Beattie Watkinson

Services engineer: Atelier Ten

Services engineer (post transfer of services): CPC

CDM, Tweeds

Arborcultural consultant:

Arups Landscape (sub-consultant to muf)

Horticultural consultant:

Julie Bixley (sub-consultant to muf)

Commissions outside the main contract

Coordinator: muf architecture/art LLP

(lead consultant)

Literary consultant: Urban Words,

Yemisi Blake

Product design: Platform Two,

Royal College of Art

Graphic design: Axel Feldmann, Objectif

Internet sources

‘muf is enough’, Jay Merrick, Independent Newspaper

'Barking Town Square', Igloo, 9 June 2008

Books and magazines

‘Barking Town Square’ in, RIBA Awards 2011, Christine Murray, Rory Olcayto and others, Architects Journal vol. 233 no. 22, 2011 June 16

‘Barking Town Square’ in, Architecture 11: RIBA buildings of the year, Tony Chapman, (London : Merrell, 2011)

‘Barking Town Square, Barking & Dagenham, London (muf)’, by Claes Sorstedt and Anna Baldini, AD profile: 197. Architectural Design vol. 79, no. 1, 2009 Jan./Feb. p. 22-23

‘Specifier’s choice: Barking Town Square; Architects: MUF’ by Sutherland Lyall, AJ Specification 2007 Jan., pp. 14-21

‘Regenerating Barking’ by Kieran Long, Architects Journal vol. 226, no. 9, 2007

Sept. 13, p. 23-35

‘Exhibition. Barking: a model town centre’, Joshua Bolchover (On the exhibition curated by MUF and Kieran Long which was at the Barking Learning Centre 12-27 September) Architects Journal vol. 226, no. 12, 2007 Oct. 4, p. 10

‘Barking town square, London', A+T Collective Spaces: In Common 3, no. 27, 2006 Spring p. 40

‘Barking Town Square, Barking’ in Gritty Brits: new London architecture, Raymund Ryan (Pittsburgh : Carnegie Museum of Art, 2006)

The Architectural Assemblage: A Dialogical Investigation of Barking Town Square, Thomas Bernard Kenniff UCL PhD, 2013

'Identity in Peripheries: Barking and its Others', Thomas Bernard Kenniff

in Peripheries, R Morrow and G Abdelmonem (eds), (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2012) pp.40-53.

'Barking Town Square', Regeneration & Renewal, 21 September 2007

'The Regeneration of Barking Town Square', New Start, 9 March 2008

'Barking', A10 (Netherlands), March 2010

'Town Square: The Toast of Europe', Barking & Dagenham Recorder, 8 March 2008

'European Prize for Public Urban Space 2008', Topos, June 2008

‘Square Dancing at Barking Central’, Ellis Woodman, Building Design, 27 November 2009